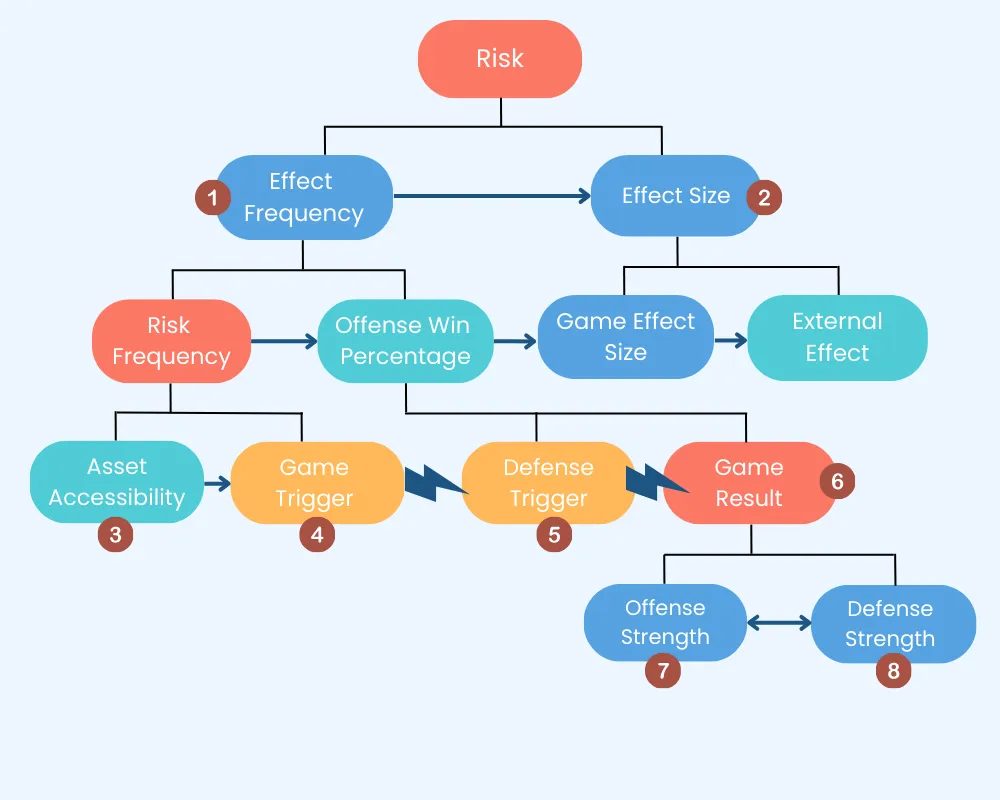

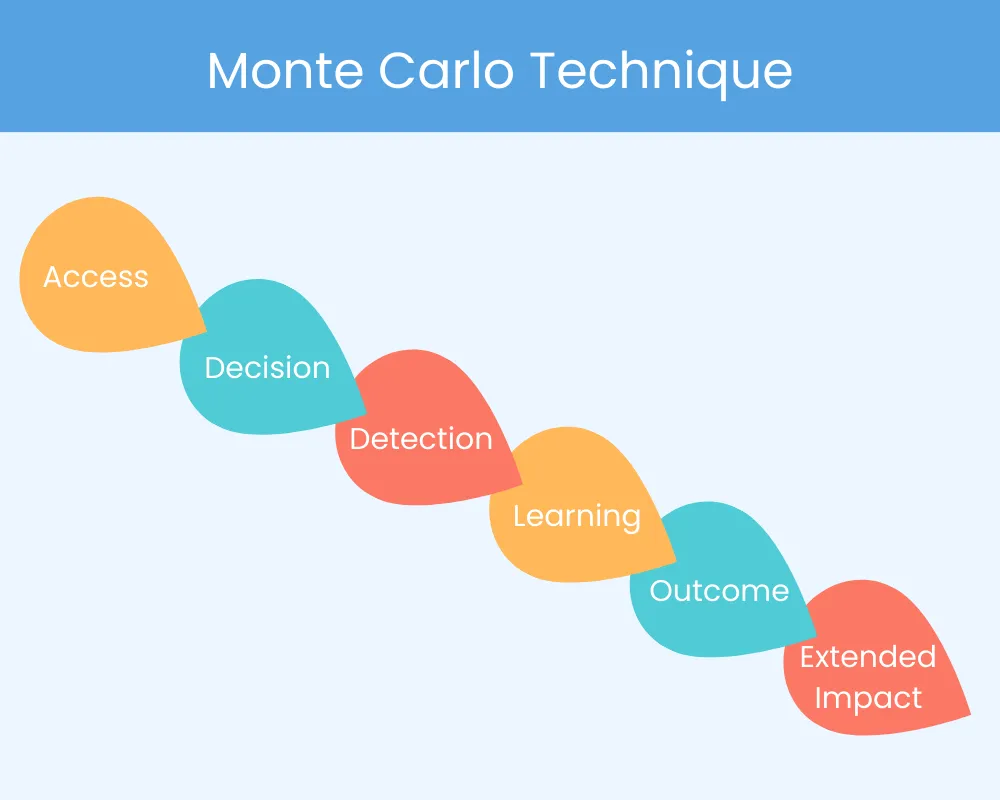

At the outset, the Defense will apply a segregation control to conceal the asset or make it inaccessible. It may also attempt to influence the Offense’s business case through deterrence controls, by reducing the perceived benefits of the attack and/or by increasing the perceived costs and the threat of a defensive reaction.

For example, if we are the Offense aiming to supplant a competitor in a specific market niche, the competitor (the Defense) may try to hide its key customer data, protect distribution channels, or lock in partners through exclusive agreements, making the target market less accessible and reducing the attractiveness of our business case.

The Offense, conversely, may attempt to bypass segregation barriers, increasing its knowledge of the asset and the Defense, patiently gathering insights step by step, much as a skilled observer learns patterns of behaviour before planning a course of action. In our example, this could involve gradually learning how the competitor operates— understanding its pricing strategy, customer acquisition methods, and operational weaknesses — so we can craft a more effective entry strategy.

The Offense may also be encouraged by a culture of experimentation within the enterprise to disregard the Defense’s deterrent measures. In our scenario, a culture that rewards experimentation might push us to test unconventional marketing tactics or alternative product bundles, even if the competitor tries to discourage new entrants through aggressive pricing or contractual pressure on suppliers.

The Offense may also launch an unconventional attack that remains invisible, succeeding simply because the Defense never recognises that the game has begun. Detection capability, therefore, becomes a crucial defensive asset. In practice, this could mean entering the market through a new customer segment or an indirect channel that the competitor overlooks — allowing us to gain traction before the Defense realises that its position is being challenged.

Once this “knowledge game” is in motion, the outcome depends on the relative strength of the resources and learning capabilities deployed by both sides. If two companies are competing in a market segment, the likely winner is the one that first understands emerging customer needs and anticipates competitor moves. Organisations built for learning and rapid knowledge transfer, such as fractal organisations, hold a strategic advantage.

Even after the game is played, the Defense may still recover part of the loss through reactive controls, while the Offense, if it has prepared multiple options, can pursue the most advantageous path (a form of option thinking).

Strong stakeholder-management skills are essential for both sides: the Defense will attempt to minimise reputational impact, while the Offense will seek to leverage early wins to build momentum and strengthen stakeholder support. The competitor may still try to regain ground by improving its offering or engaging in defensive communication. Likewise, early wins in the target niche can help us secure broader internal support from stakeholders, investors, or partners, enabling further expansion.